And what does it amount to, everlasting remembrance? Sheer vanity and nothing more.

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 4.33

When you think of Stoic artwork, what do you think of? Maybe a bust of Marcus Aurelius, or a memento mori illustration with a smiling skull? Or perhaps you’re drawing a blank, wondering if there is even such a thing as Stoic art. In fact, there is a long but somewhat hidden tradition of artwork inspired by Stoic ideas.

The ancient Stoics believed that the fine arts (musical performance, painting, literature, etc.) have a place in a well-lived life. Art is something that pretty much everyone loves in some format—it’s deeply embedded in human nature. I have previously covered the relationship of Stoicism to music and stories, and I’ve shared a wonderful guest essay from Tim Iverson on Stoicism and art. Let’s continue this theme and explore one of the most prominent artistic genres that could properly be called Stoic.

The tradition of vanitas artwork, which peaked around the 17th century, was concurrent with and born from the Neostoic philosophical movement. As we’ve discussed previously regarding Neostoic music, this was a time of philosophical flowering following the disastrous religious wars ravaging Europe at the time. Endless wars, recurrent plagues and huge technological and social changes roiled the continent, making this a time of dangerous upheaval and uncertainty. Intellectuals—tired of so much religious division and looking for inspiration and common ground in the classical patrimony of ancient Greece and Rome—found solace in the timely warnings of Stoicism to prepare for death and embrace the intransience of life. An artistic movement was born that prized somber reflection on the human condition, which we know today as vanitas art.

Memento Mori

If you know anything at all about Stoicism you probably know about its memento mori tradition, which encourages us to think frequently about death (our own and that of others). The point is not to be morbid or sad, but the opposite: preparing for death makes us strong and courageous, and it also encourages us to appreciate the gift of life, making the most of every day. Death is a natural part of life and is nothing to fear. When we learn to accept human mortality and face death gracefully, we can truly live life to the fullest.

For the record, Stoics did not invent this idea. Both Socrates and Epicurus were well-known for their thoughts on death, and it was common currency among the ancient Greeks (and later Romans). But the Stoics took the remembrance of death to a whole new level. Seneca, in particular, wrote ad nauseum about the acceptance of death. (And apparently in this case he also practiced what he preached: when ordered by Nero to commit suicide, Seneca lectured his friends on calmly facing death as the life slowly drained from his body.)

I’m not going to feature too many Senecan lines on death because it’s literally all over his work—open a page at random and you are likely to find something about mortality. But here is a nice passage, heavy with symbolism that would later be frequently used by artists:

I ask you this: wouldn't you say a person was quite stupid if he thought that a lamp was worse off after it was extinguished than before it was lighted? We too are extinguished; we too are lighted. Betweentimes there is something that we feel; on either side is complete lack of concern. Unless I am wrong, our mistake is that we think death comes after; in fact, it comes both before and after. Whatever was before us is death. What difference is there between ending and simply not beginning? Both have the same result: nonexistence.

Letters on Ethics, 54.5

And a passage on war and ruin that must surely have felt piercingly relevant to the Neostoics:

All humankind, now and in the future, is doomed to die; all cities that have ruled the world and all that have been trophies of some other power will someday disappear from sight, wiped out by varied forms of ruin. Wars will destroy some; others will be swallowed up by desuetude, and peace that turns to idleness, and that which is most ruinous to great resources—luxury. All these fertile plains will someday be covered up by some sudden incursion of the sea, or engulfed by subsidence of the earth into an unexpected cavern. Why, then, should I complain? Why should I be sad to go just a moment sooner than the end decreed for nations and peoples?

Letters on Ethics, 71.15

But in both Stoicism and the later vanitas tradition, it’s not merely the remembrance of death but primarily the contextualization of death that leads us to accept our mortality. Death is a natural process. We are part of the natural world. Therefore we are subject to the same processes as every other part of the natural world and we have no reason to get upset about dying. Here are some consoling thoughts on this topic from Marcus Aurelius:

Consider what it means to die, and that if one considers death in isolation, stripping away by rational analysis all the false impressions that cluster around it, one will no longer consider it to be anything other than a process of nature, and if somebody is frightened of a process of nature, he is no more than a child; and death, indeed, is not only a process of nature but also beneficial to her.

Meditations, 2.12

Also call before your mind, one after another, the many people whom you yourself have known. This man, after paying his last respects to that, was then laid out himself, and the one who laid him out was laid out in his turn, and all in so short a time. In a word, never cease to observe how evanescent are all things human, and how worthless: today a drop of mucus, and tomorrow a mummy or a pile of ash. So make your way through this brief moment of time as one who is obedient to nature, and accept your end with a cheerful heart, just as an olive might ripen and fall, blessing the earth that bore it and grateful to the tree that gave it growth.

Meditations, 4.48

Nature has looked to each thing's ending no less than its beginning and its course in between, as does a boy who throws a ball into the air. What good is there for the ball in rising up or harm for it in falling down and even striking the ground? What good is there for the bubble in being blown or harm for it in being burst? And the same is true of a lamp.

Meditations, 8.20

You’ll notice that Seneca and Marcus speak not just of death but of impermanence, change, and the fleetingness of time. This too is a key feature of memento mori and its contextualization in nature. Everything changes, everything passes on, everything participates in the cycles of the natural world. The transition between life and death is just another day at the office for nature.

All things proceed according to schedule: they must be born, grow, die. Everything you see passing above us, all that seems to so solid beneath our feet, will crumble away; each thing has its own senescence. Nature sends them all away, after different spans yet to the same place. That which is, will not be. Not that it perishes; rather, it is dissolved. For us, being dissolved is perishing, for we are looking at what is nearest to us. Our dull wits are pledged to the service of our bodies, and look no further than that. We would bear our own end and that of our loved ones with greater courage if we perceived that life and death, like everything else, come and go by turns. Compounds are dissolved, dissolute elements compounded, and in this way does the eternal craftsmanship of all-regulating God exert itself.

Seneca, Letters on Ethics, 71.13-14

Constantly reflect on how swiftly all that exists and is coming to be is swept past us and disappears from sight. For substance is like a river in perpetual flow, and its activities are ever changing, and its causes infinite in their variations, and hardly anything at all stands still; and ever at our side is the immeasurable span of the past and the yawning gulf of the future, into which all things vanish away. Then how is he not a fool who in the midst of all this is puffed up with pride, or tormented, or bewails his lot as though his troubles will endure for any great while?

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 5.23

In the Neostoic period of the 16th and 17th centuries, artists would pick up on many of these themes to visually display death, decay, ruin, and the perils of false pride. Let’s turn now to the most well-known expression of the memento mori tradition: vanitas.

Vanitas Artwork

Vanitas is primarily associated with the Dutch masters, although it was practiced all over Northern Europe. I don’t think I need to recreate the wheel by describing this type of artwork in detail. It’s already been done many times by art historians who are much more insightful than I am. I recommend reading some of the excellent articles below to re-familiarize yourself with the vanitas paintings and artists:

Art in Context – Detailed Definition, History, and Examples

Art in Context – Best Vanitas Artwork

A few of these sources mention the influence of Stoicism on vanitas paintings, but most people are unaware of just how influential Stoicism was on this artistic movement. One scholar who does not shy away from emphasizing this connection is Melinda Latour, who in her masterwork The Voice of Virtue describes Neostoicism as “a ‘stream of thought’ that infused certain Stoic concepts—like the notion of providence, an interest in constancy, and ethical directives to follow nature—into radically new contexts” (p. 14). Speaking about Seneca’s frequent writings on death, she says,

Seneca’s imaginative descriptions of the brevity of human life—as a shining candle that flickers in the wind and is suddenly extinguished, leaving only a trail of smoke in its wake; as a theatrical farce whose act may come to a sudden close; as a stay in a hostel on a journey far from home; as a river that rushes by as quickly as time; as a slippery and uncertain surface—served as symbolic and allegorical anchors of the rich and varied corpus of memento mori and vanitas poetry, music, and art that flourished in the period of Neostoicism. Appearing in conjunction with artistic representations of a human skull, the hourglass, dying flowers, and musical instruments (sometimes equipped suggestively with a broken string or tow), these sensory markers of transience in moral poetry, polyphonic musical settings, and still-life paintings harnessed the fragile properties of sight and sound as a precarious invitation to contemplate mortality and the paradox of time and duration.

Latour, The Voice of Virtue, p. 227

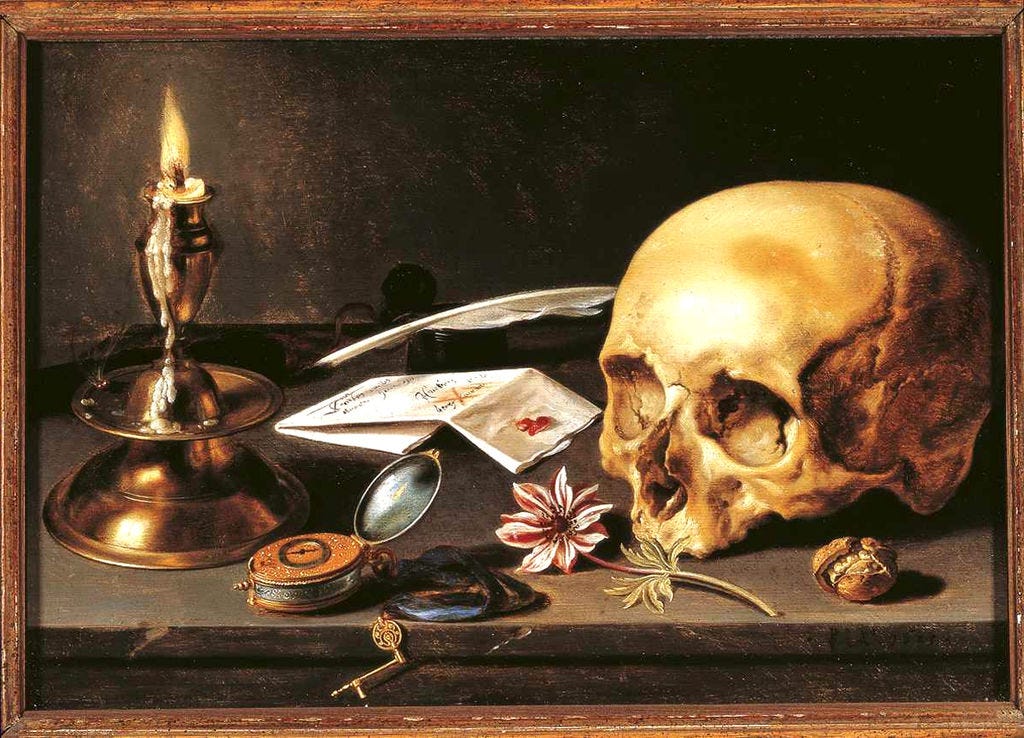

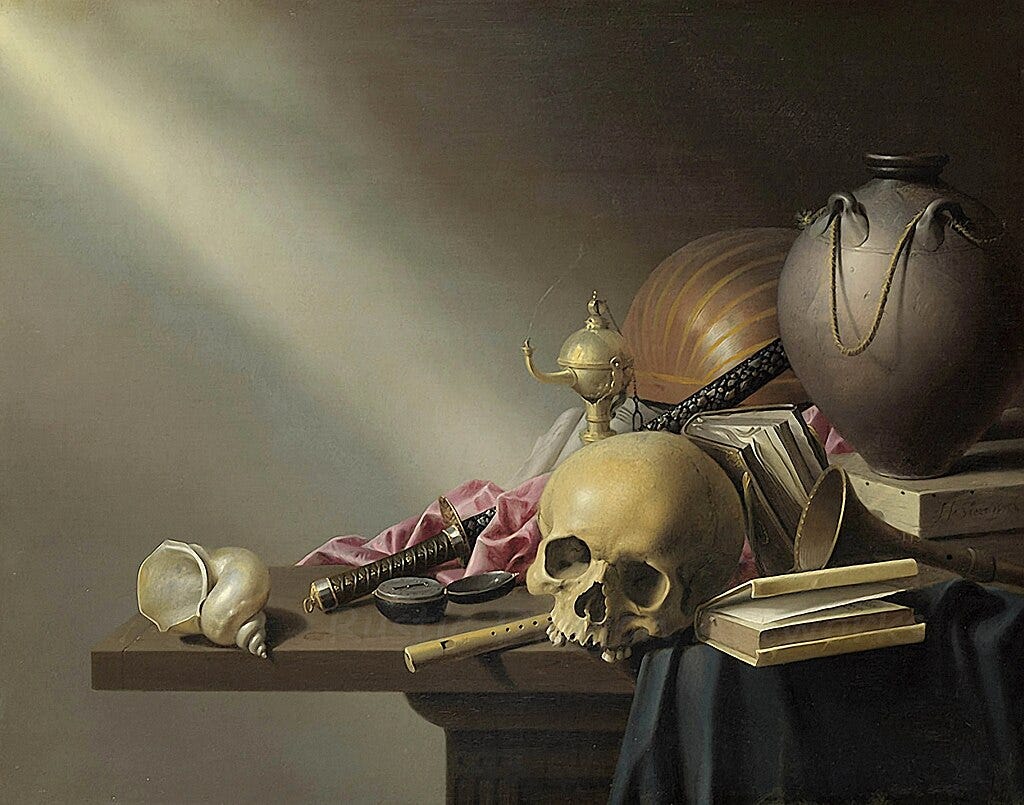

To the uneducated eye, vanitas paintings could just be cluttered still lifes, heaps of things that someone had lying around the studio and decided to paint. But in fact almost every object is carefully chosen to convey mortality, intransience, aging, time, the unreliability of our senses, or the dangers of worldly goods. Skulls are perhaps the most striking and obvious symbol, but a careful look reveals Stoic symbolism in even seemingly innocuous items:

Jewelry, coins, and other symbols of wealth serve as warnings against worldliness

Spherical objects (including balls and globes) symbolize slipperiness and instability

Masks represent death (as in Renaissance death masks) and deception (wearing a mask to fool someone)

Archeological ruins “linked the broken-down remains of human accomplishment to the natural aging process hat imprints the marks of time on all aspects of the natural world—from trees to human faces to flowers” (Latour, p. 252)

Rotting fruit and wilting flowers symbolize aging and decay

Musical instruments convey temporality as musical notes only last a moment; according to Latour, they may also “have warned of the dangers of sense decay and sense deception” (p. 228)

Windows and mirrors “underscore the moral value of perception and perspective” (Latour, p. 228)

Clocks and hourglasses (obviously) indicate the passage of time

The juxtaposition of skeletons with lively figures who are carousing and drinking indicate the foolishness of wasting time on frivolities

Seashells (which were valuable collector’s items at the time) suggest both luxury and fragility

Flickering lamps and candles show how quickly beautiful things can be extinguished

Smoke and bubbles indicate transience

Spectacles and eyeglasses suggest aging and sensory failure, but also the positive attributes of insight and perspective

I would recommend going back to look at the vanitas paintings armed with this information about Stoic symbolism—you might see them in a completely different light.

But although its popularity peaked several hundred years ago, the vanitas tradition has never completely gone away. Artists have continued to make good use of the symbols of death, from Van Gogh to Damien Hirst. But what’s changed is that the range of symbols associated with vanitas has shrunk considerably. An artist now who wants to make a point about death is working with a vastly scaled-down toolbox of pretty much just skulls and skeletons. Gone are the bubbles, flickering candles, and eyeglasses (although Fitzgerald did employ the eyeglasses symbolism in literary form in The Great Gatsby). Personally, I am ready to see some new and creative vanitas styles that nod to contemporary culture, like this one by Winston Cuevas. I think Cuevas very cleverly makes use of a pop culture reference (I can just see Wile E. Coyote setting a dastardly trap for Road Runner) and gets the point across in a whimsical way.

Of course, many contemporary artists do use a variety of symbols (such as guns and bombs) suggesting death in their artwork. But it seems to me that most of the time they are making points related to social activism—that wars should end, that weapons are bad, etc.—rather than suggesting that we pensively reflect on our mortality and appreciate our time on earth. There is certainly a place for all sorts of social commentary in our art today, but I think we are missing the more reflective strand exemplified by the vanitas tradition. Memento mori is an invitation not to activism but to contemplation and personal betterment. It’s a call to abandon the follies of worldliness and spend our time on things that really matter.

If you know of any nice contemporary versions of vanitas artwork, I would love to hear about them. For now, I think we can all still enjoy the older representations, and perhaps create space for other types of contemplative artwork. As the vanitas tradition reminds us, art can be beautiful while at the same time pointing us toward important philosophical truths.

Great read. I had been thinking about a symbol for stoicism to embrace for myself. Of course, as mentioned, a skull is often used. I was looking for something different like maybe a headland standing strong against the waves to show resilience, but as I read this for some reason the thought of buzzards feeding on a carcus came to mind or just the buzzard itself. Is that weird?

Thank you for bringing this to our attention!