A 16-year-old gets her driver’s license and gains her first real independence.

A college senior graduates and starts his first “real” job.

A young couple has their first child and buys their first house.

A veteran doctor retires after a 40-year career.

All these milestones represent major life transitions. We all know that life is a series of changes, moving over time from one phase to another—child to teenager, parent to grandparent, one career to another, etc. Sometimes our lives progress smoothly and as expected, and sometimes changes are forced abruptly and in unforeseen ways. Here is another set of life transitions, less pleasant and much more unexpected than the first:

A young adult is in a car crash and loses the use of her legs, unable to walk again.

A professional at the peak of his career is forced out of his job and unable to find a new one.

One of your parents develops Alzheimer’s and you spend years providing care, disrupting other plans you had for your life.

Life transitions can be pleasant or unpleasant, predictable or unpredictable, long-awaited or sudden and startling. But they all have one thing in common: transitions can be times of great uncertainty, anxiety, or simply weighty reflection. How can we make the best of these significant periods of our lives? How can we turn times of stress and uncertainty into periods of growth and flourishing? How can we live our lives to the fullest despite the doubt or strain that might come with change?

Let’s see what the ancient Stoics have to say.

Be prepared for anything

“Is it really true that tomorrow will never take me surprise? Surely what happens to a person without his knowledge does take him by surprise.” I do not know what will happen, but I do know what can happen. I exempt none of that from expectation: I expect it all; and if I am spared any of it, I count myself fortunate. Tomorrow does take me by surprise, if it lets me off. Yet even then it does not surprise me; for just as I know there is nothing that cannot happen to me, so also I know that none of it is certain to happen. Thus I expect the best, but prepare for the worst.

Seneca, Letters on Ethics, 88.17

Some changes are happy and exciting—getting married, retiring after a long career—while others we might dread. But while we can do our best to plan, we never know for sure what will happen or when. Perhaps something that we really looked forward to never comes to fruition, or a transition we never expected is suddenly forced on us. These can be the times when we face the bitterest disappointments or the toughest challenges.

According to Seneca, it’s the sheer unexpectedness of such things that makes them hardest to deal with. When we are expecting something pleasant and we get something unpleasant, our frustration is much deeper than if we knew along what was going to happen. His advice is to remind ourselves that nothing is guaranteed and anything can happen. We can stay emotionally flexible if we don’t allow ourselves to depend on a certain outcome for our happiness.

There are countless ways Seneca’s suggestion can apply to the hard transitions in life. You might want to start a family but you and your partner have difficulty conceiving. You might spend years preparing for a particular career and then, after starting, find out you hate it. You might be on track to retire early but then the stock market slumps and you have to wait a few more years. You might suddenly lose a loved one you had counted on spending the rest of your life with.

We have strategies for dealing with sudden transitions after the fact too (see below), but as they say an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. If you regularly remind yourself that any or all of these things can happen to you, just as they can happen to everyone else, you will not be as devastated if one of them does happen.

And if you’re lucky enough that everything in your life always goes to plan…wait a minute, that doesn’t happen to anyone. No one’s life always goes exactly the way they expected. So plan for your plans to go awry, and become comfortable with the fact that unexpected transitions will surely be a part of your life.

Welcome change

Is one afraid of change? Why, what can come about without change? And what is nearer and dearer to universal nature? Can you yourself take a hot bath unless the firewood suffers change? Can you be nourished unless your food suffers change? Can anything else of value be accomplished without change? And do you not see, then, that change in yourself is of a similar nature, and similarly necessary to universal nature?

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations, 7.18

This quote from Marcus Aurelius is so piercingly beautiful and accurate, I don’t have much commentary to add. I would recommend meditating on this passage daily during periods of transition. Humans are parts of the universe, and everything in the universe experiences constant change. Therefore humans experience constant change. The logic is devastatingly simple and yet can be so hard to accept. In order to contextualize the change that is happening in your life, you might want to sit for a while with these questions:

What’s new? What is different that needs adapting to?

What remains the same? What elements of yourself and your life can carry you through this transition?

What’s timeless? What elements of nature, the cosmos, and human nature can you depend on remaining unchanged?

In his Meditations Marcus also helped himself cope with change and challenges by reflecting as an impartial observer on the human condition:

A fine reflection from Plato. One who would converse about human beings should look on all things earthly as though from some point far above, upon herds, armies, and agriculture, marriages and divorces, births and deaths, the clamor of law courts, deserted wastes, alien peoples of every kind, festivals, lamentations, and markets, this intermixture of everything and ordered combination of opposites. (7.48)

Constantly reflect on how all that comes about at present came about just the same in days gone by, and reflect that it will continue to do so in the future; and set before your eyes whole dramas and scenes ever alike in their nature which you have known from your own experience or the records of earlier ages, the whole court of Hadrian, say, or of Antoninus, the whole court of Philip, or Alexander, or Croesus; for in every case the play was the same, and only the actors were different. (10.27)

Clearly Marcus found comfort by remembering that these transitions are simply a natural and inescapable part of our lives. They can and do happen to everyone. Rather than fighting against them or feeling like we are unfairly targeted, we should remember that they are simply neutral occurrences in the life of a human. These occurrences and transitions are neither good nor bad in themselves; they simply are. It’s what we do with them that counts. Which leads us to our final recommendation…

Make the best of things

In the face of everything that happens to you, keep before your eyes those who, when the same things happened to them, were at once distressed, bewildered, and resentful. And where are they now? Nowhere! Well then, do you want to be as they were? Why not leave these various changes to those who change and are changed, and concentrate wholly on how you are to make the best use of whatever befalls you? For then you will turn it to good account, and it will serve as material for you. Only pay attention, and resolve to act rightly in your own eyes in all that you do; and keep in mind these two points, that how you act is of moral significant, and that the material on which you act is neither good nor bad in itself. (Meditations, 7.58)

It bears repeating that what matters is not what happens to you but what you do with what happens to you. Transition periods provide raw material for us to show what kind of people we really are. Transitions can be times when we grow in unexpected ways, when we find new resources within ourselves. Epictetus says that for every challenge we face, we should look within and see what virtue we have to deal with the problem: perspective, endurance, strength, self-control, or others.

We can see that this is true because often we look back at our lives and think about what has shaped us, it’s those transitional times that stand out the most. When we first moved out on our own and had to figure out how to do things for ourselves, or when we had to cope with injury or unemployment. As unwelcome as some of these transitions may be, we can still find ways to make the best of them.

Marcus also mentions negative role models here, those people who responded badly to changes in their lives. We can probably all think of a few people we’ve known who did not handle change well and who failed to thrive in its wake. They may have felt resentful that such a thing was happening to them; perhaps they thought these things only happened to other people. Epictetus speaks directly to this experience when he says,

The will of nature may be learned from those events in life in which we don't differ from one another. For instance, when someone else breaks a cup, we're ready at once to say, “That's just one of those things.” So you should be clear, then, that if your own cup gets broken, you ought to react in exactly the same way as when someone else's does. Transfer the principle to greater matters too. Someone else's child or wife has died; there isn't anyone who wouldn't say, “Such is our human lot.” And yet when one's own child or wife dies, one cries out at once, “Oh poor wretch that I am.” But we ought to remember how we feel when we hear that the same thing has happened to others. (Handbook, 26)

It's easy to be logical and objective when someone else has a problem, but when the problem strikes us we find it difficult to be so clear-eyed. We can easily be consumed by anger, resentment, or self-pity. Our task, then, is to call on those philosophical principles we’ve studied, remind ourselves that this is what we’ve been preparing for all along, and rise to the occasion of being a good person during a difficult time.

When the time comes for you to act, will you quail? Now is the moment to suffer a fever; may it proceed as it should; to undergo thirst, may you undergo it in the right spirit; to undergo hunger, may you undergo it in the right spirit. Isn't that within your power? (Discourses, 3.10, 8-9)

Transitions are no different. When it’s time for us to face unemployment, will we face it in the right manner? When it’s time for us to slide slowly into old age, we will do so in the right spirit? When it’s time to end or begin a relationship, to welcome a new person into our life or gently let go of a loved one, will we undergo these changes in the right way? The change will happen whether we like it or not—that is a given of our human experience. But it’s up to us whether we go along graciously and welcome the change, or whether we resist.

Concluding Thoughts

When we learn to see transitions as events that happen to everyone, we ease the emotional burden of anxiety and resentment that often sneaks in unnoticed. And when we open ourselves to the opportunities that a transition can bring, we can even find peace or joy in ways we never expected.

So we could sum up our discussion today in three bullets:

Prepare yourself for a wide variety of transitions before they happen.

Remember the universe is in constant transition, and therefore human life is in constant transition.

Make the best of a difficult time by identifying what virtues you can bring to bear and how you can grow through this transition.

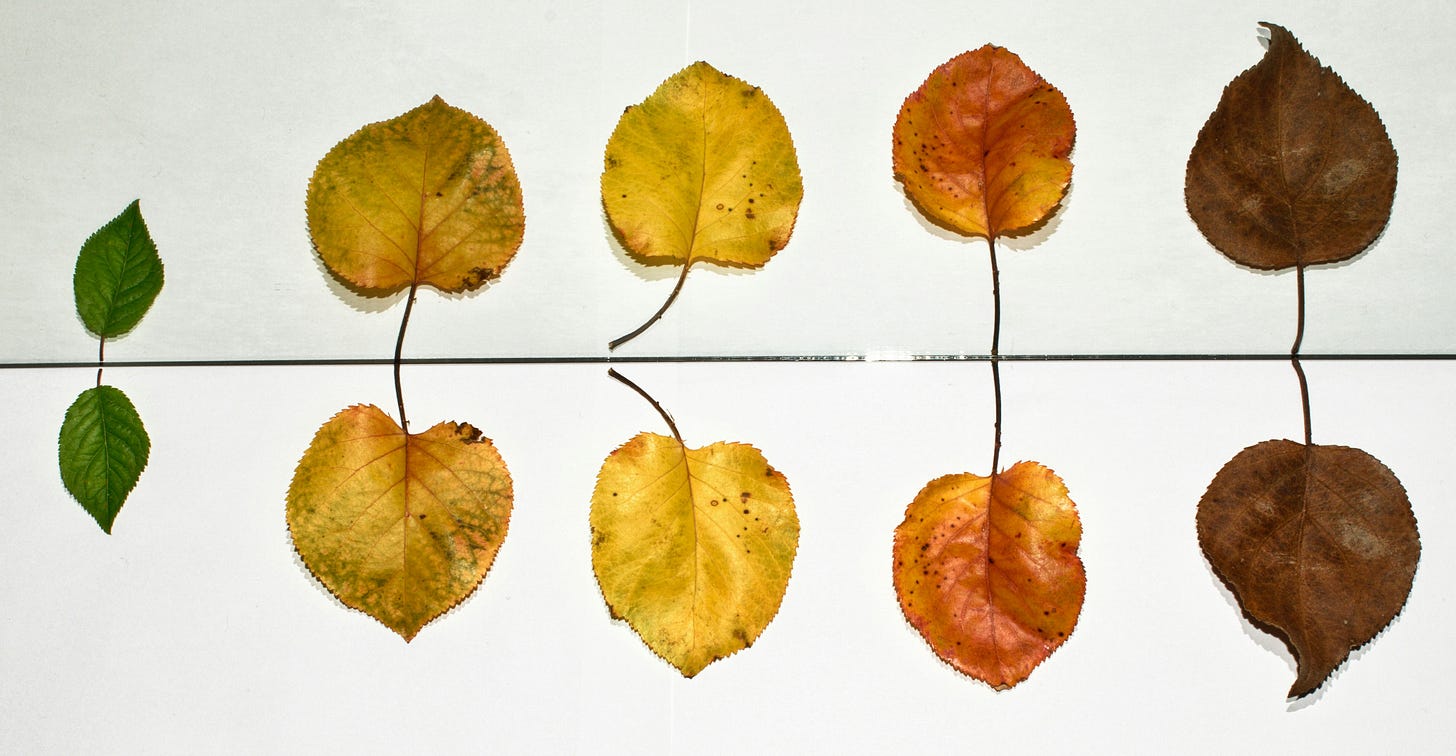

Change is nothing personal. It’s just the way of the universe. And in its own way, change is rather miraculous—the fact that the elements of one thing can be rearranged into the organized whole of another entity is pretty amazing. So let’s try to develop an appreciation for those transition periods, which can be difficult but also beautiful. Though our own bodies may age, though our own lives may be irrevocably altered, these changes also bring renewal and rebirth. So here’s another poignant thought from Marcus Aurelius (Meditations, 7.25) to close:

All that you now see will be changed in no time at all by nature that governs the whole, and from its materials she will make new things, and from their material new things again, to keep the universe forever young.

Photo credit: Tolga Ulkan on Unsplash

I absolutely loved this post. From personal experience, every major disruption in my life was actually a phenomenal turning point. For example, I consider MS diagnosis as one of the best things that ever happened to me. Being a teenage alcoholic and fighting through addiction has been one of the best things I have ever happened to me. I have not used since August 10 1982, specifically at 2 o’clock in the afternoon before walking into detox. And the list goes on.

Now granted, I have not always handled those transitions as smoothly as I could have, and sometimes it takes a bit of time to gain the proper perspective, but ultimately I have prevailed.

Thank you again. I truly enjoy your writing.

Wonderful post, thank you!