To begin, a disclaimer: in some ways I am really not interested in contemporary debates about free will, which often seem like ego trips by famous philosophers. I hate it when people argue just for the sake of arguing about abstract topics that don’t impact anyone. I’ve always thought it bizarre that philosophers could argue about whether free will exists, then go eat dinner as if nothing happened.

At the same time, I often find myself extremely troubled by real-world issues of moral accountability—sometimes paralyzed by sadness at the unfairness of life. If someone was abused as a child by the people who were supposed to love him, and surrounded by a culture that validates criminality, and does not have any positive role models who show a different path for a good life, can we blame him at all for adopting a life of crime? It would seem not to be his fault. And what about in our own lives, where we’re making an effort to become better people, but we may have past influences that lead us astray? Where does personal moral accountability begin and end?

People who are much smarter than me have been thinking about these questions for a very long time, and I’ll go out on a limb and say there are no easy answers to these difficult issues. But that doesn’t mean there is no way to answer them at all. And because questions of free will and agency do ultimately have these important real-life impacts, I try to carefully consider them, no matter how disorienting they are.

As you may remember from last year’s posts about Michael Tomasello’s book The Evolution of Agency, I prefer to discuss agency rather than free will, since free will seems to imply that we could ever be completely free of constraints, which is not the case. Also I think speaking in terms of agency opens up more avenues of exploration, because it’s less polarizing and lends itself to considering the wide range of psychological, situational, and evolutionary factors that contribute to agency. This is especially true when considering an ancient ethical theory like Stoicism, where “free will” did not exist as the specific concept we talk about today. (For people who want to nerd out on this topic, I highly recommend Michael Frede’s A Free Will: Origins of the Notion in Ancient Thought, posthumously edited by A.A. Long.) However, since today’s author couches his arguments in terms of free will, I will also be using that term.

Free Agents: How Evolution Gave Us Free Will is Kevin Mitchell’s very helpful guide to making sense of agency and free will in real life. Mitchell is a neuroscientist by training (at Trinity College in Dublin), and this book covers a lot of ground from the basic biology of life through the evolution of cellular and mammalian agency to state-of-the-art neuroscience research. I highly recommend it for anyone interested in these topics who enjoys high-quality pop-academic research.

I particularly appreciate that Mitchell is willing to take on the thorniest moral questions head on, which Tomasello explicitly shied away from in his book. Mitchell actually seems to relish this discussion, saying that he began the entire project with the moral implications of agency in mind. And here’s where he takes a stand that few other contemporary thinkers are willing to take:

I present a conceptual framework that aims to naturalize the concept of agency by grounding the otherwise vague or even mystical-sounding concepts of purpose, meaning, and value. The truth is that, far from being unscientific, those concepts are crucial to understanding what life is, how true agency can exist, and what sorts of freedoms or limitations we actually have as human beings. (p. xi)

That’s right: we have a neuroscientist who is willing to explore agency in terms of values and the meaning of life! Later in the book we see that Mitchell does lean on ancient virtue ethics to support this mission (particularly Aristotle and Cicero’s Stoic-inspired work On Duties), but he also relies on a broad range of modern sciences from chemistry to genetics to brain imaging. In other words, this is exactly the kind of book we all need to read right now.

This is a conceptually dense work and there’s no way I can cover most of it here. So as usual, I’m just pulling out a few of the key points that I think can provoke or advance our thinking on the topic. (Or perhaps I should say: points that have advanced my own thinking on the topic.) I will do this by presenting four misunderstandings about free will that Mitchell addresses in the book. Afterwards, I will discuss my own interpretation and how these points have helped me sort through some of the difficulties of moral agency.

Misunderstanding 1: Science proves that free will doesn’t exist

“It’s fashionable these days to claim that “free will is an illusion!”: either it does not exist at all, or it is really not what we think it is. (p. 18)

Mitchell’s response: As a neuroscientist, Mitchell is especially well-placed to respond to arguments against free will at the level of cognitive and neuroscientific research. He emphasizes that many of the studies once touted as “proving” that our minds are at the mercy of external or subconscious forces are weak or unreliable: “The seminal publications are characterized by small samples, questionable statistical methods, and, in some cases, outright fraud” (pp. 250-251):

I am not willing to give up on [free will] so easily. In this book I argue that we really are agents. We make decisions, we choose, we act—we are causal forces in the universe. These are the fundamental truths of our existence and absolutely the most basic phenomenology of our lives. If science seems to be suggesting otherwise, the correct response is not to throw our hands up and say, “Well, I guess everything we thought about our own existence is a laughable delusion.” It is to accept instead that there is a deep mystery to be solved and to realize that we may need to question the philosophical bedrock of our scientific approach if we are to reconcile the clear existence of choice with the apparent determinism of the physical universe. (p. 18)

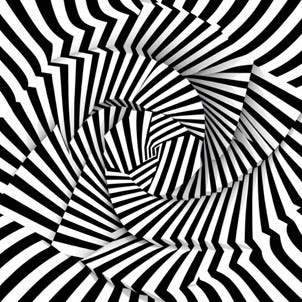

Mitchell compares the sensationalist research on free will to our everyday experience of optical illusions. Consider, for example, this image:

When you look at the picture, do you see a rosette of swirls popping out toward you, or do they spiral downward and away from you? Or perhaps both at the same time? In this classic example of an optical illusion, our eyes aren’t quite sure what to make of the dizzying pattern. We are visually thrown off balance, switching back and forth between two different perspectives.

But, Mitchell argues, just because our eyes are temporarily confused or fooled doesn’t mean they don’t function wonderfully well most of the time. If our eyes didn’t perform well in daily life, they wouldn’t be much use to us in staying alive and flourishing. The fact that we depend so much on our eyes is what makes these occasional trompe l’oeil experiences so salient.

In much the same way, according to Mitchell, studies purporting to show that we are helpless against environmental factors are inaccurate and misleading:

Even if we can sometimes be primed by external factors, this does not mean that we never make our own conscious decisions for our own reasons. And just because patients with brain lesions draw and report inaccurate, even fanciful explanations of their behavior under pathological circumstances, this does not mean that the system is not well suited to draw accurate explanations under normal circumstances. (p. 251)

So how do we reconcile the difficult concept of free will with the realities of our lives, which include many environmental influences? Mitchell presents an extended answer throughout Free Agents. Here we’ll examine just three points:

Life has purpose, meaning, and value

We can distinguish between factors that determine and influence

Free will doesn’t mean a complete absence of constraints

So let’s discuss the meaning of life.

Misunderstanding 2: There is no meaning to life

Mitchell’s response: Life has purpose, meaning, and value.

It’s almost verboten today among psychologists and neuroscientists to speak of telos, or an animating purpose of life. Mitchell, however, has no such qualms and wholeheartedly embraces the ancient idea that living things have a telos, which is to continue living. This shouldn’t be confused with the position that the universe itself has a telos. He makes it very clear that while living organisms have a purpose (staying alive), that purpose is simply the result of physical processes that happened to give rise to the organism—there’s no grand plan to the universe.

As living things became more sophisticated, evolving from single-celled organisms to more complex invertebrates and later vertebrates, life was guided by the invisible hand of natural selection. Organisms that fulfilled their telos of staying alive and procreating took over the world. As Mitchell puts it,

Once life does exist, everything changes. The universe doesn’t have purpose, but life does. Natural selection ensures it…Before life emerged, nothing in the universe was for anything. But the functionalities and arrangements of components in living organisms are for something: variations that improve persistence are selected for on that basis, and ones that decrease persistence are eliminated. (p. 42)

Because living things always have the telos of staying alive, Mitchell argues, it only makes sense to speak about agency in terms of meaning and agency. While each individual agent—each specific instantiation of a species—may not have chosen its purpose, it nevertheless has one simply by virtue of being the thing that it is:

Meaning became the driving force behind the choice of action by the organism. That choice is real: the fundamental indeterminacy in the universe means the future is not written. The low-level forces of physics by themselves do not determine the next state of a complex system. In most instances, even the details of the patterns of neural activity do not actually matter and are filtered out in transmission. What matters is what they mean—how they are interpreted by the criteria established in the physical configuration of the system. Animals were now doing things for reasons. (p. 21)

These reasons provide a framework and a guide for our actions and our agency. To speak of agency without speaking of purpose and meaning doesn’t make sense, Mitchell suggests. It’s not as if purpose needs to be any supernatural or unnatural; rather, as the ancient Greeks understood, it can be supplied by nature itself.

Misunderstanding 3: Because we are always constrained in our choices by prior causes (including genes and environment), we can never truly be free

If we are really at the mercy of a long string of prior causes that have configured our brains in a certain way, then how free can we be? The argument goes that if we were not ourselves in control of those prior causes—which include our species’ evolutionary history and our own genetics, along with the effects of our upbringing and environment and experiences—then we did not freely choose our current inclinations and desires; that is, what we want. Rather, we are constrained to act in certain ways by the shackles of our histories, conditioned to act out the next scene in the story, and not truly free to author our own futures. (p. 220)

Mitchell’s response:

Our innate psychological predispositions do not determine our behavior on a moment-to-moment basis. What they do is influence how we interact with the world and adapt our behavior to it over the course of our lifetimes. They shape how we become ourselves—the way our character and our habits emerge—in interaction with our experiences and the environments we encounter, choose, and create for ourselves. We are not passive in this process, merely acted on by causes outside our control: this process is one in which we ourselves, as active agents, play a causally effective role. (p. 229)

Mitchell likens our interactions with the environment to a delicate duet between organism and world: “The organism is meeting the world halfway, as an active partner in a dance that lasts a lifetime” (p. 217). I love this metaphor of a dance, where each partner responds in some way to the movements of the other. Both partners contribute to the give and take of the dance, with their actions impacting each other. Yet one is not controlled by the other; they are in a sort of symbiosis, feeding off each other’s energy and innovation in an ecological tango. And crucially, organisms are able to alter their behavior in response to new dance steps developed by their environment. In simpler organisms, this might take place only at the level of natural selection, as more adaptive behaviors are selected for through generations of genetic changes. In more complex organisms such as mammals and especially humans, this often takes place at the level of individual organisms through processes we call learning and development:

Our innate predispositions influence our actions, experiences, and responses to those experiences. The interplay between these factors, driven by the ongoing exercise of our own agency and expressed through the idiosyncracies of each of our lives, shapes the emergence of our characteristic adaptations: the habits, heuristics, policies, projects, and commitments that define who we are as persons and that contribute to the continuity of our behavior as selves, through time. (p. 242)

Here Mitchell brings in a concept that is quite foreign to most contemporary discussions of free will but which Stoics will readily recognize: character. Many contemporary thinkers hesitate to bring in the concepts of character and the good life that anchored ancient Greek discussions of philosophy. But Mitchell does not hesitate to connect character to agency. In fact, he says that character is only a meaningful concept if we have agency:

Overall, then, the idea that our innate personality traits determine our behavior is frankly simplistic. In essence, this view sees people as passively driven by their biological predispositions, on a moment-to-moment basis, like robots that are tuned one way or another. The character viewpoint, by contrast, puts people as agents at the center of a process of engagement and coevolution with the world, actively developing the habits, attitudes, policies, and mature tendencies that make us all who we are. These views can be reconciled by recognizing that there will be an interplay between our innate traits and the trajectory of development of our character. (pp. 242-243)

By the way, this is also one of the key differences between the Aristotelian and Stoic positions on agency: while both Aristotelians and Stoics acknowledge the importance of external factors in shaping character, Stoics are much more practical about adults being able to actively improve their own character. Aristotle doesn’t offer much in the way of remediation if you had the misfortune of being born in the “wrong” family. Stoicism, on the other hand, sees ethical development as a lifelong project, one that we each take an active role in. Even if you were raised in a way that led to unhappiness and ethical misunderstanding, as an adult you retain the capacity reflect on your life and make changes.

Misunderstanding 4: The presence of constraints invalidates the idea of free will

The arguments [above] suggest that we do have a hand in shaping our own character; not all the prior causes are things that were out of our own control. However, it could still be argued that the presence of any constraints, right now, regardless of where they came from, invalidates the idea of real free will. This idea hinges on an absolutist notion: we are only truly free if we are completely free from any prior constraints. Then, we not only can choose what we do based on what we want, but also can freely choose what we want, unfettered by … well, anything. Once you dig into this notion a bit, it quickly becomes incoherent, revealing a dualist notion of the self that evaporates when examined closely. (p. 244)

Mitchell’s response: Mitchell argues that the concept of a self without constraints is absurd; a self is created by constraints. Even at a physical level, “continuity is the defining property of life…The organism is not a pattern of stuff; it is a pattern of interacting processes, and the self is that pattern persisting” (p. 245). An organism would not exist without the physical boundaries and chemical processes that both constitute and constrain it.

At a psychological level—and remember that our minds are still part of our physical bodies—we are formed by all the experiences that have shaped our lives. Our brains are physically changed with every experience we have, so a person as a psychological entity would not exist without the physical changes that have taken place as their brain interacted with the world around them. Without your prior history and all those prior causes you wouldn’t exist at all. There would be no “self” to make decisions and take action in the world.

A person with the kind of free will envisaged by some—completely free of the influence of any prior causes—could do whatever, but not whatever they want because they wouldn’t have any wants. They would have no reason to do anything in particular or anything at all, in fact. They would have no continuity as a person through time and would not really exist as a self at all. Our goals and knowledge and commitments provide us with enduring reasons for action and the ability to act on them. “We” only exist as selves extending through time. (p. 246)

So while we sometimes feel trapped or frustrated by our past histories and mental habits, they are the framework for human cognition and action. We may bemoan them as constraints, but they function psychologically similar to the way our bones function physically—without them we would be formless and unable to do much of anything. Thinking of it this way, we can see that our personal history, with all of its limitations, isn’t just a constraint, but rather a support for rational agency in the world.

We are not absolutely free, nor would we want to be—this is not a coherent notion at all, in fact. But we do have the capacity for reflective cognition, which means our subconscious psychology is not always opaque or cryptic to us. We have powers of introspection and imagination and metacognition that let us identify and think about our own beliefs and drives and motivations, examine our own character, and consciously adopt new goals or set new policies that guide our future behavior. We have, in short, the capacity of self-awareness…We have, in real time, the means to intentionally adjust our behavior by selecting the objects of our attention and the different options for action that we consider and prioritize. (p. 219)

Concluding Thoughts

Like the ancient Stoics, Mitchell stresses that mature humans have the capacity to reflect on our lives and change things that aren’t going well for us. We don’t get to choose the circumstances we grow up in—our family, our neighborhood, all the influences on our lives—but as adults we have the ability to evaluate our current circumstances and take steps to improve ourselves.

However, I would point out that doesn’t mean anyone can do anything at any time. Just like a non-weightlifter can’t suddenly decide to lift 300 lbs, and someone who has never tried to diet before can’t suddenly decide to resist every dessert at the Christmas party, you can’t just wake up one day and decide to do things completely differently than ever before. You have to take small steps toward your ultimate goal. Given the previous circumstances of our lives, some things are only possible for some people, and not everything is possible for everyone at every moment.

But we retain the capacity to make an initial decision to change, based on where we are right now. We can take a small step in the direction of mental and emotional health today, which changes our initial conditions when we make our decision tomorrow. The beauty of agency is that we can make new decisions at any moment, based on any changes in our circumstances. In this way, we can slowly establish new habits, new thought patterns, and (eventually) even new character traits.

We can’t change our initial starting point in life—that’s outside of our control and was already determined for us, falling into the category of prior causes. This is just one more reason why we should try to be understanding rather than contemptuous toward people who make different decisions from ourselves. Everyone is starting from different conditions, and some people started out with great disadvantages, so they have more ground to cover than others. Life is truly unfair.

Returning to the example above, of the young man whose role models all joined gangs and who doesn’t think he has any other path to a successful life, we can see that his choices are constrained by the difficult circumstances of his life. He couldn’t just decide tomorrow to go to college and become an accountant.

But that doesn’t mean his choices are already determined; he retains the capacity to reflect on his life and respond based on new circumstances that arise. In prison he might read a book by a Roman Emperor named Marcus Aurelius, or he might cross paths with one of the amazing people bringing Stoicism to the incarcerated. (If you’re interested in getting involved in this area, check out the amazing work of Santara Gonzalez, Andy Small, and Rob Colter.) And sometimes just one small change—creating a new set of conditions in which to take our next decision—can make a world of difference.

Good read! I like the Stoic attitude of being able to improve ourselves gradually over time, in terms of our mindset. That being said, maybe that desire to improve ourselves is just another determined trait in us that some of us have and others don’t. 😅

You explained this so very well! Thanks, Brittany!